The participation of American Indians in the Great War has been little researched so that information is sparse and often inaccurate. For the two first chapters of the following section, I relied on two major sources: Michael L. Tate's article published in the Western Historical Quarterly in October 1986 entitled "From Scout to Doughboy: The National Debate over Integrating American Indians into the Military, 1891-1918." Michael Tate's article was of great use in treating the first chapter dealing with the debate over the integration or segregation of American Indians in the military and with the draft. Although I also used Michael Tate's study for the second chapter on the actual military and civil service of American Indians in the Great War, I relied more heavily for this question on Russel L. Barsh's article published in Ethnohistory in the summer of 1991, entitled "American Indians in the Great War."1

As I had been struck from the beginning of my research by the importance of American Indian symbols in the Great War, I shall devote the third chapter on this aspect of the presence of American Indians in WWI. My two main sources of information here were all written material, but especially American newspaper articles, published during the Great War and reviving old stereotypes about American Indians, and visual representations in the form of army insignia, graffiti, and memorials. Finally, in the last chapter, I shall analyze the direct consequences of the involvement of American Indian soldiers in the Great War.

If the question of whether American Indians should be integrated into White companies or segregated had been raised in the past, it became a crucial matter in April 1917 when the United States entered the war. The Canadian example was used by both sides of the debate but was not of much help since it was a mixture of integration and segregationin Autumn 1915, because of the high casualty rate and the shrinking of White volunteerism, the Canadian government started recruiting Indian companies (segregation) which were attached to White regiments (integration).2

Another question that did not seem to bother those who debated on integration vs. segregation was that of the status of American Indians vis-à-vis the draft in 1917. It is difficult to evaluate how many American Indians were citizens at this date, yet it is certain that many of them were not. I will thus rapidly review the different measures that conferred citizenship on American Indians before the 1924 Citizenship Act in order to understand how they were or refused to be drafted in the American Army.

Support for all-Indian units was threefold, coming from the Board of Indian Commissioners, Congress and the ever-present Joseph Kossuth Dixon. Among the opponents to segregated units were the current and one former Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, the newly-created Society of American Indians and Captain Pratt.3 As integrationists attracted more influential support than segregationists, their view eventually won. Nonetheless, some Indian units were actually created, especially from Oklahoma, where the percentage of Indian population was much higher than in any other state, thus establishing a de facto segregation.

1.1. State of Affairs in April 1917

1.1.1. Segregationists4

The "segregationists," those who supported the constitution of Indian units, were typical turn-of-the-century philanthropists whose main argument was concern for the dying Indian. Their enthusiastic campaign for Indian regiments was the result of both goodwill and a feeling of superiority.

Board of Indian Commissioners Edward E. Ayer contributed a great deal to the promotion of Indian regiments. For this businessman concerned with efficiency, here was a way to reduce unemployment on reservations and to employ the skills of educated Indians. He started campaigning even before the United States entered the war, drawing support from the Board of Indian Commissioners and from Indian Bureau superintendents and school officials.

Ayer's position was given momentum when two bills were introduced in Congress in April and May of 1917. The first one was introduced by Representative Julius Kahn of California on April 30, 1917 (HR 3970) and called for ten or more regiments of Indian cavalry. Upon enlistment, Indians would receive a certificate of citizenship without losing their tribal rights. Two weeks later, Senator Boies Penrose of Pennsylvania introduced a similar bill in the Senate.

Joseph K. Dixon, bolstered by his experience with American Indians during the Wanamaker expeditions, took on the promotion of the idea of Indian regiments in the military. At a meeting of the House Committee on Military Affairs called by Kahn in July 1917, he read 30 pages of testimony from American Indians as well as Whites. One of his most important supporters was the Omaha Indian anthropologist Francis La Flesche from the Bureau of American Ethnology. Dixon argued in support of his position by using the example of segregated regiments used by the AlliesGurkha, Nigerian or Senegalese. But interestingly enough, Dixon did not refer to Black regiments in the American army, as if he considered Senegalese, Gurkha and Nigerian to belong to the "indigenous" rather than the dark-skinned category.

According to the Boston Hampton Committee in a report about American Indians issued during the Great War in March 1919, "it was hoped by many of them [Indians] that separate units of Indian troops might be formed, but that proved to be impossible, owing to their relatively small numbers and lack of training in certain branches of the service."5 John Lynn, U.S. Marshal for the western district of New York also reported that most of the 5,000 would-be Iroquois volunteers strongly preferred all-Indian companies.6 It is hard to determine what the general opinion was among American Indians on the question of separate or integrated units because no one took the trouble to ask them their position. As for the position of the Iroquois volunteers, there was a very good reason: the Iroquois had declared war on Germany independently from the United States.7 It is also probable that the Boston Hampton Committee's statement essentially represented the opinion that White educators were promoting amongst their students.

Like segregationists, people opposing all-Indian units did so out of good willexcept perhaps the Secretary of War who was mainly concerned with military efficiency.

Cato Sells, Commissioner of Indian Affairs from June 1913 to May 1921 and Francis E. Leupp who held the same position between 1901 and 1909,8 opposed all-Indian regiments from the outset. For Cato Sells, Indian units were "not in harmony with our plans for developing the Indian's citizenship." Indians should thus enlist in the war "as the equal and comrade of every man who assails autocracy and ancient might, and to come home with a new light in his face and a clearer conception of the democracy in which he may participate and prosper."9

Integrationists benefited from the support of Captain Pratt. This was not negligible in the sense that Richard Henry Pratt argued from first-hand experience, having been in charge of Indian scout companies from 1867 to 1875. He was also in the position to be heard as former founder and director of the Carlisle Indian School. According to the memoirs he finished dictating to his daughter in 1923, Pratt was already aware in 1867 of the dichotomy existing between the dignifying experience Native Americans had as scouts in the army and the desolation of their life on reservations.10 By 1917, after many years of work with American Indians, R.H. Pratt knew that there was no such thing as separate but equal: "It would be far better for them to be recognized as individual men than as masses."11

Less buoyant than Captain Pratt but of a higher military rankand hence more influentialwas Major General Hugh L. Scott, the Chief of Staff. For Jennings C. Wise whose 1931 book on American Indian history has a chapter on American Indians in the Great War, Hugh L. Scott was the "man who probably knew more about Indians in 1917 than any other."12 Wise was most likely exaggerating but he was partly right in the sense that Hugh L. Scott had once commanded Indian soldiers of Troop L, Seventh Cavalry at Fort Sill, Indian Territory in the 1890s.13 Scott's refusal of separate units was unquestionable but was apparently based more on an idealistic view of a unified country at a time when the melting-pot was beginning to be questioned, than on any specific concern for the Indians. It is also interesting and characteristic that Scott's sympathy for Indianswho were, after all, very few in numberwent hand in hand with total dismissal of the case of Black Americans:

This time there should be no Polish, Armenian, or Russian regiments, as in the Civil War; no "fought mit Siegel," no "sons of Garibaldi"; nothing but homogeneous American troops. The separate Negro organizations we cannot avoid.14

Secretary of War Newton D. Baker's opposition to the segregationist plan was more based on the analysis of the failure of the experiment of all-Indian scout companies of the 1890s. Unswerving in his adamant position, he succeeded in convincing Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane who rather favored all-Indian units.15

The Society of American Indians played a crucial role in the success of the integrationist view. Most influential members of the S.A.I. like Arthur Parker or Gertrude Bonnin (Zitkala-Sa) strongly favored the participation of American Indians in the European conflict as a way to demonstrate American Indian patriotism and they widely used the S.A.I.'s publicationthe American Indian Magazineto publicize their position. But if American Indians were to show their worthiness as Americans, the United States had to acknowledge such by treating them as human beingsnot as some type of wild west show heroes.16

The decision was thus taken by Secretary of War Baker to integrate Indians in the Army, which was a concrete victory for the young Society of American Indians. Nonetheless, different factors conspired to bring about the formation of some all-Indian units.

The largest contingent of American Indians who would enlist in the Great War came from Oklahomabetween 5,000 and 6,000 according to Russel Barsh.17 Oklahoma had been a state for only ten years in 191718 and had been roughly delineated in the 1830s as the "Indian Country" to which all Indian populations hampering settlement in the East would be relocatedthe so-called Five Civilized Tribes, Shawnee, Seneca, Wyandot, Modoc and later Cheyenne, Southern Arapaho, Kiowa, Comanche, Wichita, Kickapoo, Sauk and Fox, etc. Meanwhile settlers continued to move west and it did not take more than fifty years before they began looking longingly at the Indian lands of the Oklahoma area. In 1885, Congress voted a law authorizing the Bureau of Indian Affairs to buy Indian lands and on April 22, 1889, the district of Oklahoma was opened to settlement by President Benjamin Harrison, receiving the official status of Territory in May.19

Even after thirty years of White settlement and several laws reducing Indian reservations in Oklahoma, in 1917, American Indians still represented roughly one third of the state population,20 as well as one third of the United States' overall Indian population.21 The 36th Division of the American Expeditionary Forces that arrived in France in July 1918 was composed of approximately 20,000 men of the Texas and Oklahoma National Guards22 and it was no surprise that some 600 American Indians served in this division. Half of them had already served in the Oklahoma National Guard before the war and they were especially well represented in the Company "E" of the 142d Infantry Regiment as well as in the 358th Infantry Regiment, both of which would later be widely publicized for the heroism of their Indian "warriors."23

With the Sioux representing a sizeable proportion of the Dakota population in 1917, there were some largely Lakota units, such as Battery B of the 130th Field Artillery, Battery C of the 147th Field Artillery and companies of the 351st and 355th Infantry Regiments.24 There were also cases of American Indians voluntarily staying together in units where Whites were in majority, such as the North Dakota Indians who formed a "Border Patrol" scouting unit.25

However, as most American Indians were minorities in their states in 1917, most of them were scatteredintegratedthroughout the army. At the same time, the debate around integration vs. segregation and concerning the actual formation of all-Indian units seemed to take it for granted that all Indians of the United States in 1917 were draftable, which was not the case as we shall now see.

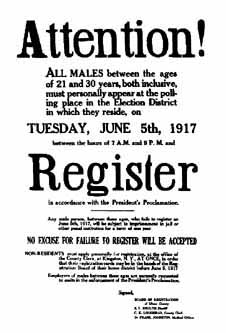

According to the Selective Service Act of May 18, 1917, registration was to be conducted the same way for "all male citizens, or male persons not alien enemies who have declared their intention to become citizens, between the ages of twenty-one and thirty years, both inclusive."26 There are no exact figures telling how many Indians were citizensor "intending" to become citizensin 1917 but it seems clear that a large number of American Indians were enlisted illegally, which of course gave rise to draft incidents.

In his 1918 report, Commissioner of Indian Affairs Cato Sells acknowledged that "considerable uncertainty arose in connection with the first registration as to what constitutes Indian citizenship." Superintendents were thus given general rules for "doubtful cases." According to these rules, the following could be considered citizens of the United States: those Indians who held fee patents under the conditions of the 1887 Dawes Act and of the 1906 Burke Act ; Indians who had "adopted the habits of civilized life" away from their tribe, and all children of citizen Indians.27 A short survey of the different measures that gave citizenship to American Indians will show how difficult it is to know how many of them were citizensand thus subject to the draftin 1917.

Some early treaties signed by the thirteen original States specified that Indians who abandoned their tribal relations and adopted "civilization" could become State, and American, citizens. In the 1830s, treaties were signed with the Five Civilized Tribes postulating that any tribal member who wished to remain in Georgia, Alabama or Mississippi could take an allotment and be regarded as a State citizen.28 Both cases thus granted citizenship to those Indians who gave up their "tribal citizenship," acknowledging the existence of a two-level citizenship for Indians, the last one being exclusive of the first .

"All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the States wherein they reside."29 Contrary to appearances, the 14th Amendment of 1868 did not apply to American Indians. A December 1870 Senate resolution declared that tribal Indians were not citizens because they were not subject to the jurisdiction of the United States as it was meant in the Amendment.30 They were not subject to this jurisdiction because they were already subject to the jurisdiction of their tribe. This was ironic reasoning at a time when federal troops and White settlers did not hesitate to assert federal authority over the tribes that were in their way.

In the case Elk v. Wilkins of 1884, John Elk, an Indian who lived a "civilized" life in Omaha, Nebraska, was denied citizenship and voting rights on the ground that his unilateral decision to sever the ties with his tribe was not sufficient to grant him citizenshiphe also needed a specific act from Congress acknowledging his situation.31 Here we have a reversal of policy"civilization" is no longer a sufficient element for citizenship when Indians attempt to use their first right as a citizen: the right to vote.

In 1890, Congress voted the Indian Territory Naturalization Act through which any member of an Indian tribe in Indian Territory could apply for citizenship in federal court without losing his tribal citizenship.32 This measure was to be expanded in March 1901 by another vote from Congress declaring every Indian in Indian Territory to be a citizen of the United States.33 No need to see any good will here: this was only a way to raise the number of Oklahoma citizens in order for the Territory to apply for Statehood.34

The Dawes Act of February 8, 1887 tied Indian citizenship to the ultimate proof of civilization: individual property. The Indian became an American citizen as soon as he received his allotment. The Act also declared that Indians could become citizens if they had separated from their tribes and adopted the ways of civilized life, without this ending their rights to tribal or other property.35 The Allotment Act reflected the philanthropic spirit of the late 19th century, but at the same time it introduced an ambiguous element into the status of American Indians who now had a double citizenship: tribal and American.

In 1906, the Burke Act postponed citizenship for the Indians until the end of the trust period, except for a provision allowing citizenship to be granted to an Indian who was deemed "competent and capable of managing his or her own affairs."36 Once again, here was a reversal of policy which, as complicated as things already were, made it now nearly impossible to determine who was a citizen and who was not.

This list of measures which contributed towards extendingor limitingIndian citizenship is certainly not exhaustive. Yet it provides a panorama of the non-systematic aspect of the process. It also shows that citizenship was used by policy-makers as the gauge of Indians' progress on the scale of civilizationthe only debate being whether citizenship should be given as a first step toward assimilation or as an acknowledgement of an already-completed process.

Consequently, it is no surprise that no definite census of the Indian citizen population exists for the years before the Great War. However, we know that approximately two-thirds of all American Indians were already citizens before the Citizenship Act of 1924.37 It can thus be estimated that at least half of the Indian populationthat is approximately 130,000 peoplewere officially American citizens in 1917.38

2.2. American Indians and the Draft

As previously stated, all Indian men who were citizens in 1917 were subject to the draft. Yet, even President Wilson was not sure about this and had to ask confirmation from Provost Marshal Enoch H. Crowder.39

The problem was of course that it was very hard to determine who was a citizen and who was not. Hopefully, draft authorities were helped by American Indians themselves who "manifested the utmost good spirit in assisting," 2,000 of them having been so willing to serve that they had volunteered for the American and Canadian armies even before the draft had been put into effect. Draft boards composed of the superintendent of the agency, the chief clerk and the physician were constituted on each reservation. All American Indians were allowed to volunteer, whether they were citizens or not.40

Local draft offices were instructed that if there was any doubt concerning the Indian's status, he should be considered as a non-citizen. However, draft authorities apparently took advantage of the ambiguous status of American Indians to enlist some who would not have been legally draftable otherwise: those who were non citizens, had dependants or had failed the medical examination.41 The confusion concerning the Indians' legal status revealed itself fully in the official service records of the members of the Eastern Cherokee Band. When asked if they were United States citizens, some said yes, others said no, some wrote "ward," and one answered with a question mark.42

American Indians who refused the draft were sent to jailwhether they were right or not in the grounds of their refusal. Families and tribal councils started writing letters to the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington and to courts so that the BIA ordered an investigation. But local BIA offices dragged their feet until the end of the war and never really investigated anything.43

Carlos Montezuma, one of the founders of the Society of American Indians, strongly opposed the enlistment of non-citizen Indians. He clearly explained his position in a letter he wrote to Simon Kahanados, an American Indian from Wisconsin who had asked him whether Indians could be drafted or not. Montezuma's position is interesting because it highlights the double standard used toward American Indians who were American enough to be canon fodder but not American enough to be citizens. Montezuma also took advantage of the situation to further demonstrate his adamant opposition to the Indian Bureau:

I do not think it is just for the Superintendents of the Indian service to get Indian young men to go to war. Why, because the United States Government has not given freedom to these young men. The Indian young men would be fighting for the United States government that is keeping them as slaves and not citizens of their own country. It does not look right to me or to those who love justice. The Indian is competent to be a soldier but not a citizen. That does not look right either. Indians that does not vote and lives from the Government he cannot (be) drafted or forced into the war.44

Draft incidents resulted from the refusal of certain American Indians to enlist and they were widely exaggerated and distorted by the newspapers in an atmosphere of patriotic wartime hysteria.

The first incident occurred in June 1917 with Northern Navajos and Utes threatening the building and people of the draft registration offices. In both cases, the Indians protested because they believed they would be sent directly to combat troops across the Atlantic.45

It went further in early 1918 when a mass protest by nearly all 150 men and women of the Nevada's Goshute Reservation was interpreted as a revolt against the draft process. These people were actually much less concerned by the draft than by the neglect they suffered from their superintendent and from the BIA. Yet, the news was rapidly spread by the New York Evening Mail that German agents were behind the troubles, and by the Nevada State Journal which evoked a general Indian uprising throughout the Great Basin.46

A few months later that summer, some 200 Creeks from east-central Oklahoma reportedly killed three White farmers to protest against the drafting of their sons. Once again newspapersin this case the New York Timeswere quick to draw conclusions about treason. The revolt was considered by Indian office people as "systematic pro-German propaganda practiced among the tribes."47 While this distortion was grotesque, it is nonetheless interesting because it shows that most newspaper articles relating to the war were little more than government releases.

Some tribes also resisted the draft because they wondered how they could serve the American Army while not being American citizens. They feared that their tribal rights might be endangered in the process. Such was the case for the Pamunkey and Mattaponi Indians of Virginia. The Attorney General's office ruled that, not being citizens, they could not be drafted. Yet, some volunteered for the Army, thus proving that their opposition to the draft was not based on an absence of patriotism.48 The Iroquois went further.

Arthur C. Parker, a Seneca and prominent member of the Society of American Indians, drafted the Onondaga Nation's declaration of war against the "Austrian and the German Empires" and he wrote to a Seneca leader, urging him to follow the example of this fellow member of the Iroquois Confederacy because it would

establish your independent right to act as a Nation and not as a ward-bound tribe that had no powers of a Nation. The Senecas have lost none of their sovereignty since 1812 and a war declaration would serve to emphasize your status. The fighters could then enter the United States Army the same as now.49

The Onondagas, one of the once powerful Iroquois Confederacy had decided to declare war on Germany because some of their number had been badly treated in Berlin in 1914 when the war broke out. They were part of a Wild West Show and were beaten, insulted, and put in jail. They were eventually released but they did not forget this disgraceful incident. The Onondagas thus drafted their declaration of war in July 1918, recalling for this purpose a treaty signed in 1783 with George Washington that recognized them as an independent people. A few weeks later, another member of the Iroquois Confederacy, the Oneidas, followed the example of the Onondagas.50

Unlike the Civil War, when the Iroquois had a hard time being accepted as soldiers in the Union Army on the basis of their status as American Indians, the question did not seem to raise any problem in 1917. After fifty years of assimilation, American Indians were considered, if not citizens, at least potential soldiers and the question only remained how they would be integrated in the army. Ironically, by this time, the Iroquois decided they did not want to be American soldiers but Iroquois soldiers fighting for the American Army.

Part II, WWI and its Consequences: Chapter II: American Indian Service in WWI

1 . Michael L. Tate. "From Scout to Doughboy: The National Debate Over Integrating American Indians into the Military, 1891-1918." Western Historical Quarterly. 17:4, (October 1986), pp.417-37. Russel L. Barsh. "American Indians in the Great War." Ethnohistory. 38:3 (Summer 1991), pp.276-303.

2 . Michael L. Tate, op. cit., pp.425-26.

4 . In the absence of other sources to be found in France, this paragraph is essentially an exposé of Michael Tate's analysis in the article cited in the note above.

5 . A Brief Sketch of the Record of the American Negro and Indian in the Great War. Report of the Committee of Information of the Boston Hampton Committee. March 1919, p.4.

6 . Michael L. Tate, op. cit., p.428.

7 . The matter will be dealt with further. Nelcya Delanoë &Joëlle Rostkowski. Les Indiens dans l'Histoire américaine. Nancy: Presses universitaires de Nancy, 1991, p.125.

8 . Francis Paul Prucha. The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians. Abridged edition. Lincoln &London: University of Nebraska Press, 1986, Appendix A.

9 . Cato Sells to Mr. Henry M. Tidwell, Superintendent of the Pine Ridge Reservation, SD, February 4, 1918, p.2. Y.M.C.A. Historical Archives.

10 . Richard Henry Pratt. Battlefield and Classroom: Four Decades with the American Indian, 1867-1904. Edited and with an introduction by Robert M. Utley. New Haven &London: Yale University Press, 1964, pp. ix, 7.

11 . Quoted by Michael L. Tate, op. cit., p.427.

12 . Jennings C. Wise. The Red Man in the New World Drama. A Politico-Legal Study with a Pageantry of American Indian History. Edited and revised from the 1931 edition by Vine Deloria, Jr. New York: MacMillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1974 (1971), p.323.

13 . Michael L. Tate, op. cit., pp.419-20.

14 . Wise quotes from a book written by Hugh L. Scott but does not give the bibliographic reference. Jennings C. Wise, op. cit., p.323.

15 . Michael L. Tate, op. cit., p.427

16 . Hazel W. Hertzberg. The Search for an American Indian Identity: Modern Pan-Indian Movements. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1971, pp.170-71.

17 . Interview with Russel Lawrence Barsh. January 16, 1994.

18 . Oklahoma was the 46th State to be admitted in the Union on November 16, 1907. Mary Beth Norton, et al. A People &A Nation: A History of the United States. Third edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990, Appendix A-25.

19 . Elise Marienstras. 1890: Wounded Knee ou l'Amérique fin de siècle. Paris: Editions Complexe, 1992, pp.80-81.

20 . Interview with Russel L. Barsh. January 16, 1994.

21 . Francis Paul Prucha, op. cit., p.305.

22 . "Les Américains au combat." In 1917-1987: 70e Anniversaire de l'entrée en guerre des Etats-Unis d'Amérique. Secrétariat d'Etat aux Anciens Combattants, 1987.

23 . Michael L. Tate, op. cit., p.430. Russel L. Barsh, op. cit., p.282 and note 11 p.298.

24 . "Author Seeks WWI Stories." Lakota Times. March 31, 1993.

25 . Russel L. Barsh, op. cit., p.282.

26 . The Selective Draft Law and the President's Registration Proclamation. New York: National Bank of Commerce in New York, May 1917, Section 2, p.13.

27 . Report of Commissioner of Indian Affairs Cato Sells. September 30, 1918. In The American Indian and the United States: A Documentary History. Vol. II. Ed. Wilcomb E. Washburn. New York: Random House, 1973, p.875. Cato Sells quotes these general rules given to each superintendent in 1917:

I. Indians whose trust or restrictive fee patents are dated prior to May 8, 1906, are citizens by virtue of section 6 of the act of February 8, 1887 (24 Stat. L., 388).

II. Indians whose trust or restrictive fee patents are dated May 8, 1906, or subsequent thereto and who have received patents in fee for their allotments are citizens by virtue of said section 6 of the act of February 8, 1887, as amended by the act of May 8, 1906 (34 Stat. L., 182).

III. Section 6 of the act of February 8, 1887, both before and after its being amended by the act of May 8, 1906, provided that:

"Every Indian born within the territorial limits of the United States who has voluntarily taken up, within said limits, his residence separate and apart from any tribe of Indians therein, and has adopted the habits of civilized life, is hereby declared to be a citizen of the United States, and is entitled to all the rights, privileges, and immunities of such citizens..."

IV. The solicitor of this department has held that where Indian parents become citizens upon allotment their minor children became citizens with them, and that children born subsequent thereto were born to citizenship.

28 . Vine Deloria, Jr. &Clifford M. Lytle. American Indians, American Justice. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1983, pp.218-19.

29 . Mary Beth Norton, et al., op. cit., Appendix A-15.

30 . Francis Paul Prucha, op. cit., p.231.

31 . Vine Deloria, Jr. &Clifford M. Lytle, op. cit., p.220. Francis Paul Prucha, op. cit., p.231.

32 . Vine Deloria, Jr. &Clifford M. Lytle, op. cit., p.220.

33 . Francis Paul Prucha, op. cit., p.260, pp.305-06.

34 . Philippe Jacquin. "De l'indigène au citoyen: l'Amérindien sort de la réserve." In Les Etats-Unis à l'épreuve de la modernité: Mirages, crises et mutations de 1918 à 1928. Ed. Daniel Royot. Paris: Presses de la Sorbonne nouvelle, 1993, p.143.

35 . "General Allotment Act." February 8, 1887. The American Indian and the United States: A Documentary History. Vol. III. Ed. Wilcomb E. Washburn. New York: Random House, 1973.

36 . Francis Paul Prucha, op. cit., p.267, p.298.

37 . Ibid., p.273. Nelcya Delanoë &Joëlle Rostkowski, op. cit., p.135.

38 . Michael L. Tate, op. cit., p.429. Russell Thornton. American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History Since 1492. Norman &London: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990 (1987), p.160.

39 . Michael L. Tate, op. cit., p.429.

40 . Jennings C. Wise, op. cit., p.320.

41 . Russel L. Barsh, op. cit., pp.280-81.

42 . John R. Finger. Cherokee Americans. The Eastern Band of Cherokees in the Twentieth Century. Lincoln &London: University of Nebraska Press, p.39.

43 . Interview with Russel L. Barsh. January 16, 1994.

44 . John William Larner, Jr., ed. The Papers of Carlos Montezuma, M.D. Including The Papers of Maria Keller Montezuma Moore and The Papers of Joseph W. Latimer. (Microfilm) Roll 4. Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources Inc, n.d., C.R.H.E.U.

45 . Michael L. Tate, op. cit., p.429. Russel L. Barsh, op. cit., p.281.

46 . Michael L. Tate, op. cit., p.429.

47 . Russel L. Barsh, op. cit., p.281. Michael L. Tate, op. cit., p.429.

48 . Walter L. Williams. Southeastern Indians Since the Removal Era. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1979, p.39.

49 . Arthur Parker to Walter Kennedy, August 5, 1918, quoted by Hazel W. Hertzberg, op. cit., p.175.

50 . Francis Whiting Halsey. The Literary Digest of the World War. (10 vols.) Vol.1. New York &London: Funk &Wagnalls Company, 1920, pp.233-34.