Huachuca

Illustrated, vol 1, 1993:

Huachuca

Illustrated, vol 1, 1993: Huachuca

Illustrated, vol 1, 1993:

Huachuca

Illustrated, vol 1, 1993:

chuca Illustrat

chuca Illustrat

Military Intelligence in the American Southwest:

Pioneering Aerial Reconnaissance

Pioneering Aerial Reconnaissance

chuca Illustrat

The use of the newly developed military asset, the airplane, for reconnaissance missions was first undertaken in the Philippines and then along the Mexican border between 1913 and 1915. Later, during Pershing's 1916 Punitive Expedition into Mexico in pursuit of the bandit-turned-revolutionary Pancho Villa, the First Aero Squadron was deployed to support Pershing with aerial reconnaissance. Their purpose was thwarted however, when the planes were unable to reach the altitudes necessary in the mountains of northern Chihuahua. Instead the aviators were relegated to a role offlying dispatches from headquarters to the roving columns of cavalry.

Lt. Brooks flying over the 24th Infantry at Colonia Dublan, Chihuahua, on 5 July 1916.

One of the aviators who served with the 1st Aerosquadron during the

Punitive Expedition was Lieutenant John B. Brooks, a former 10th Cavalry

officer at Huachuca who transferred to the Signal Corps' aeronautical section.

He left a description of his operations in Mexico.

One of the aviators who served with the 1st Aerosquadron during the

Punitive Expedition was Lieutenant John B. Brooks, a former 10th Cavalry

officer at Huachuca who transferred to the Signal Corps' aeronautical section.

He left a description of his operations in Mexico.

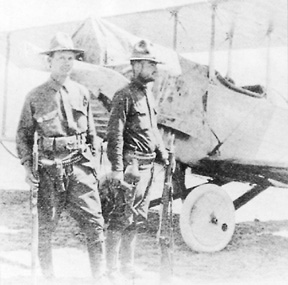

Soldiers guard aeroplane in the 1916 Punitive Expedition.

The JN4's (or Jenny's) were the original planes that went into Mexico. The First Aero Squadron, which was the first unit of Aviation that we ever had in this country, was formed at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. They flew their eight planes from Fort Sill to San Antonio, Texas, for permanent station and that was the first unit cross-country flight that was ever made in this country. In the meantime they had built a field for them, just outside Fort Sam Houston. They had hardly settled down there when Villa attacked Columbus in March of 1916. Immediately they put their airplanes on flatcars. They came out to Columbus and they grubbed out a field there. They flew from there right into Mexico, right away. Well,. there were a number of mountains down there, particularly Cumbre Pass that was eight or nine thousand feet above sea level, and these little airplanes with 65 horsepower engines didn't have the stuff to get up and get over those mountains. They were cracking them up right and left because they hadn't had experience and there were no fields down there.

You had to find a place to set down. You wanted to land as close to the troops as you could. So you might hit some sagebrush and bend a wing and you were out of commission for some time. So those original eight airplanes didn't last very long. I did not go in with the original group. I was still in training at North Island. But they saw that they're going to have to have a bigger more powerful airplane and they were going to have to have additional pilots, so they grabbed our class and graduated us a little bit early so we could go right down there. We were graduated early in June and sent right to Columbus and we arrived just about the same time the new airplanes arrived. They were known as Curtis B-2s and it was quite a wonderful airplane for that day and generation. It had a V8, 160 horsepower motor. It was the most powerful aviation motor that had ever been built in this country at that time, and the airplane was a fine, sturdy airplane, but like everything that's brand new there are always little bugs in it that have to be worked out through operational experience. Our biggest trouble that had to be solved right away was the wooden propellers. There were no steel propellers. They were made of laminated wood with one layer right after another to build up the propellers with the proper curves. They were made at Hammons Port, New York. They came down here to Columbus, New Mexico, and it was so dry that, after they'd been in use for a little while, that lamination, the glue all dried out and the propeller would fly to hell and gone in the air. You got down the best way you could. So we had really quite a time with those planes and I operated in Mexico twice. They used to rotate us down there for about six weeks at a time and I served one six week period down at El Vaya and another one at Columbia de Blanco.

A squadron of military aircraft used in the Pershing

Punitive Expedition.

... We didn't have any machine guns mounted; we had no bombs. We were solely a reconnaissance outfit and most of the time used by General Pershing to bring back negative information. In other words, he was just as happy to know that the Carranzista troops were not at a certain place. His hands were tied by the State Department and he couldn't make war where he wanted to after the first couple of months. They had him surrounded by all sorts of regulations and the Carranzista troops were getting more bold all the time and getting right in close to our front flank. He would get a bit of information saying that there were 250 Cavalry over at such and such a ranch. He'd send us out and we'd go over there and we would fly low around the corral of this ranch. If there were only five horses in there, why chances were that there weren't any Cavalry there.

"Assembling an Aeroplane at Fort Bliss, Texas."

Photo by W. H. Horne, El Paso, Texas.

We had message bags ... and they had a long red streamer on them. They were weighed with shot and you could do pretty accurate hitting within fifty yards where you wanted to get them. The red streamer would call attention to the fact where they landed and you could then pick them up.(68)

Aviators Rader, Brooks, Royce and Christtie at Colonia

Dublan, Mexico, 5 July 1916. National Archives photo 94-UM-203781.

Observation balloons were used during the Civil War, with negligible results. The first use of aerial intelligence gathering in its modern sense had its American beginnings in the skies of the American Southwest, an area that would be the site of training for aerial photo reconnaissance personnel and the development of unmanned aerial reconnaissance craft in the years to come.

2d Lieut. Frederick John Gerstner, 10th Cavalry,

was detailed from Fort Huachuca to be a student officer at the Aviation

Section, Signal Corps, in September 1914. He drowned on 21 December 1914

when his aeroplane crashed enroute from San Diego to Los Angeles. He was

the 18th aviator to give his life in the interest of government aviation

since Lieut. Selfridge fell to his death at Fort Myer, Virginia, in 1908

testing the first aeroplane for the Army. Photo from obituary contained

in Annual Association of Graduates, USMA, 1915.

2d Lieut. Frederick John Gerstner, 10th Cavalry,

was detailed from Fort Huachuca to be a student officer at the Aviation

Section, Signal Corps, in September 1914. He drowned on 21 December 1914

when his aeroplane crashed enroute from San Diego to Los Angeles. He was

the 18th aviator to give his life in the interest of government aviation

since Lieut. Selfridge fell to his death at Fort Myer, Virginia, in 1908

testing the first aeroplane for the Army. Photo from obituary contained

in Annual Association of Graduates, USMA, 1915.

Footnote: