W. Reginald Wheeler

China and the World War

.

CHAPTER I

THE ATTACK UPON THE CHINESE REPUBLIC FROM

WITHOUT, DURING THE FIRST YEAR OF THE WAR. JAPAN'S CAPTURE OF TSINGTAO AND

THE TWENTY-ONE DEMANDS

The Great War first burst forth in Europe, but its effects were felt

at once on the opposite side of the globe. These effects were both immediate

and far-reaching. Momentous as were the results of the first year of the

war in Europe, they were equally significant in Asia, and the making of

the new map of the Orient was one of the most important features of the

first stage of the great conflict.

On August 1, 1914, Germany declared war on Russia and France; just two

weeks later Japan sent an ultimatum to Germany, demanding its complete withdrawal

from its possessions in the Pacific. On August 23rd, Japan declared war;

within three months, Tsingtao , the Oriental stronghold, of the Germans,

with the co-operation of a small British force, was captured, and the Japanese

were installed in Germany's place in the province of Shantung. Two months

later, Japan presented a series of demands on China, divided into five groups,

the acceptance of which would have placed China definitely in the position

of a vassal state. After less than four months of negotiations, on May 8,

1915, China accepted four groups of these demands, leaving the fifth open

for future discussion. Thus, in the first nine months of the first year

of the Great War, Germany's political and military power were eliminated

in the Orient; Japan had taken over its possessions in China; and China

had been forced to concede to Japan extensive territorial rights, economic

privileges, and military concessions of great strategic importance. Thus

the ante-bellum situation in the Far East was entirely altered, and new

problems of international policy and relations were created. The spark struck

at Sarajevo had, indeed, kindled a world-wide flame; Europe and Asia, the

Occident and the Orient, alike were to feel its transforming force.

In order fully to comprehend the action of both China and Japan during

this period, an understanding of their development and international position

is necessary. The summer of 1914 found China still in the throes of the

attempt to gain political stability within its own boundaries; to make its

newly founded republic a stable reality. Less than three years before, on

October 10, 1911, a revolution against the existing Manchu dynasty had broken

out; on February 12, 1912, the Manchus signed their Edict of Abdication.

A republican form of government had already been set up at Nanking, with

Doctor Sun Yat-sen as Provisional President; when the Manchus abdicated,

Dr. Sun voluntarily gave place to Yuan Shih-kai, who became the first President

of the Chinese Republic. A provisional constitution was adopted and Peking

was chosen as the capital. Elections to the new National Assembly were held

in the following winter and the two houses met in Peking in April, 1913.

Ever since the establishment of the Republic, two clearly recognized parties

had been in existence; one composed of the Radicals and the Liberals, made

up chiefly of Southerners, with Dr. Sun as their leader; the other consisting

of Conservatives and the Military Party who supported Yuan. The writing

of the Provisional Constitution had been done by the Southerners; it limited

the power of the President and gave Parliament a large measure of authority.

The majority of the first Parliament were Radicals. There was much friction

between Yuan and the Assembly; it was increased by Yuan's signing, without

the consent of Parliament, a loan with the bankers of the Five Powers, including

Japan, the United States having withdrawn; by Yuan's expulsion of various

Southerners from office; and by the assassination of one of their prominent

leaders(1) in Shanghai,

Yuan's government being charged by many Southerners with his murder. Finally

the President's command to the Military Governor of one of the Southern

provinces to give up his office, together with the sending of Northern troops

to enforce the order, brought on armed resistance and the rebellion of the

summer of 1913. Nanking was captured by the Northern troops and the rebellion

collapsed. Dr. Sun Yat-sen and many of his associates fled to Japan. In

October the Assembly passed the laws which provided for the election of

the President. On October 6th, Yuan Shih-kai was elected President by the

two Assemblies for a term of five years; and on the next day, Li Yuan-hung

was elected Vice-President. The United States and several South American

republics had already recognized the Chinese Republic; now the European

Powers and Japan did the same. Thus the Republic acquired a recognized international

status.

But the drafting of the new constitution was accompanied by more friction,

and finally, on November 4th, Yuan purged the Parliament by expelling the

Radical members; the National Assembly was dissolved and an Administrative

Council was formed in its place. On May 1, 1914, a constitution designated

as the Constitutional Compact, which had been drawn up by a conference organized

in March, was promulgated. Professor F. J. Goodnow, of Columbia University,

who had been appointed Constitutional Adviser, had a large influence in

forming this instrument. This constitution gave large powers to the President,

granting him practically an absolute veto-power and the right to re-election

after a term of ten years. It provided for a One-chamber Parliament. After

drawing it up, the Constitutional Compact Conference worked out provisions

for a Council of State with the vice-president as speaker, which would act

as a legislative body until a new assembly could be elected. This Council

of State began its work on June 30, 1914. It had before it the amendment

of the laws governing the presidential elections, to make them conform to

the new compact; and the laws concerning the formation of the new Parliament.

This, then, was the situation in China at the outbreak of the Great War.

From her own viewpoint, her problems were almost entirely internal; her

whole mind was bent on the task of building up a republic in place of the

old empire. She faced enormous difficulties in the lack of a system of universal

education, of adequate transportation facilities, of modern means of industrial

production and manufacture, and of any general development of her natural

resources. She had to adjust her meagre finances to the pressure and demands

of a government of the twentieth century, and she seemed to be tending toward

an autocratic government under the guise of a republic. She had little energy

to spare for new foreign relations and, when the war broke out, as a matter

of course, she at once announced her neutrality.

There was some hope that Chinese territory would not be involved in the

military operations of the conflict; but the ultimatum of Japan to Germany

on August 15th at once brought the war to China's doors. Japan, in sending

this ultimatum, avowedly acted as the ally of Great Britain. The rise of

Japan in power and international prestige had been meteoric. In comparatively

few years she had broken away from her seclusion; had set up a monarchy

in place of a feudal state; and had definitely turned her face toward progress

and reform. In this step she was a full generation in advance of China,

from which country she had originally drawn her written language, her arts,

and much of her civilization. As a result of two victorious wars she had

sprung into the front-rank of world powers. In 1895 she had won Formosa

and the neighbouring Pescadores Islands from China; Korea had been made

independent, and the Liaotung Peninsula, including Port Arthur, had been

ceded to Japan. This last territory Japan was forced to return to China

on representations of Russia, Germany and France; but in 1905, after the

victory over Russia, Port Arthur and the Russian railways and privileges

in that section were finally won. All Russia's concessions and powers in

Southern Manchuria were given to Japan, and her paramount interests were

recognized in Korea. In 1910, Korea was formally annexed. In 1911, at the

time of the Chinese revolution against the Manchus, Mongolia became virtually

independent, and Japan began to turn her attention to the eastern and inner

portions of that province which bordered the Japanese possessions in Southern

Manchuria.

In the meantime in Europe, friendly relations were being built up between

Great Britain, France and Russia; their community of interests was evident

at Algeciras and in Persia. Japan was admitted into this friendship first

in 1902, by the formation of the Anglo-Japanese alliance, which was revised

and extended in 1905 and 1911: and, in 1907, in the agreement between France

and Japan regarding Far-Eastern affairs, which paved the way for a reconciliation

with France's ally, Russia. In 1909, the United States suggested in the

interests of the open-door that the Manchurian railways be neutralized but,

as an answer, in July, 1910, Russia and Japan entered into an agreement

to preserve the status quo(2)

without compliance with the American request. Thus in two decades the Japanese

Empire had risen to a place of equality among the great nations, and it

had gained the power to adapt and enforce her own foreign policy in the

world-turmoil produced by the Great War.

The Anglo-Japanese Alliance contained the following stipulations:

"If by reason of an unprovoked attack or aggressive action, wherever

arising, either of the High Contracting Powers should be involved in war

in defence of its territorial rights or special interests, . . . the other

High Contracting Party will at once come to the assistance of its ally

and will conduct the war in common and make peace in mutual agreement with

it."

When Japan accordingly mobilized its army and its fleet and, on August

15th, sent its ultimatum to Germany, its demands were two-fold:

"First,--- to withdraw immediately from Japanese and Chinese waters

German men-of-war and armed vessels of all kinds, and to disarm at once

those that cannot be withdrawn.

"Second,--- To deliver on a date not later than September 15th

to the Imperial Japanese authorities, without condition or compensation,

the entire leased territory of Kiaochow, with a view to the eventual restoration

of the same to China."

A reply within a week was demanded and, none being received, Japan declared

war.

Considerable uneasiness was evident in the Orient concerning Japan's

ultimate intentions, and several statements were made by Japanese statesmen

to allay these suspicions. Thus on the day Japan's ultimatum was delivered

to Germany, Count Okuma, the Premier, sent a telegram to the press in America,

saying: "Japan's proximity to China breeds many absurd rumours; but

I declare that Japan acts with a clear conscience in conformity with justice,

and in perfect accord with her Ally. Japan has no territorial ambitions

and hopes to stand as the protector of the peace in the Orient." Again,

in August 24th, he telegraphed a message to The Independent (New

York), saying in part: "As Premier of Japan, I have stated and I now

again state to the people of America and of the world that Japan has no

ulterior motive, no desire to secure more territory, no thought of depriving

China or other peoples of anything which they now possess. My government

and my people have given their pledge, which will be as honourably kept

as Japan always keeps promises."

On September 2, Japanese troops were landed on the coast of Shantung

Province from where they marched overland to Tsingtao. China's fears concerning

the possibility of its neutrality being violated seemed justified, as the

Japanese army took possession of various towns and cities in the interior,

as well as the railroad to the provincial capital; assumed control of the

means of communication; and made requisitions upon the Chinese population.

A small force of British troops were landed inside the German leased territory

and co-operated nominally in the siege of Tsingtao. On November 16, the

city surrendered and the German military and naval power in the Far East

was eliminated.

Japan now had an opportunity to survey the world situation as affected

by the war and to orient itself in relation to it. By the end of 1914 it

was apparent that the war would not end quickly: momentous changes in national

alignments were in progress; and an unequalled opportunity seemed to present

itself in Japan for satisfying various territorial and economic ambitions.

As later events demonstrated, these ambitions and aims were five in number.

First, to succeed Germany in its position and possessions in Shantung; second,

to consolidate the Manchurian territory won in the war with Russia and to

add to it a part of Mongolia; third, to gain a controlling share in the

iron output of China; fourth, to secure the military safety of Japan by

rendering impossible the lease of any of China's ports or coastal islands;

fifth, if possible, to enter into such close economic, military and political

relations with China, as to make it, with all its vast resources, tributary

to Japan. These five aims were expressed in the Twenty-one Demands served

on China on January 18, 1915.

The review of these demands by any true friend of Japan is not a pleasant

task. It is only fair to say that the liberal-minded statesmen of the Empire,

because of the international suspicion aroused, look upon these demands

with regret. Every friend of Japan and China hopes that the agreements will

be reviewed at the final Peace Conference in the light of the principles

for which the Allies are fighting.

Before the demands were presented to China there were various rumours

current concerning them. Many Japanese statements were made advocating a

more aggressive policy towards China. Perhaps the most important of these

was a secret memorandum of the Black Dragon Society (so-named from its connection

with the "Black Dragon" province of Manchuria).(3) This statement was by chance disclosed some

months after the serving of the Twenty-one Demands. After outlining the

world's situation as it affected China and Japan, it emphasized the necessity

of solving the Chinese question at once and of forming a defensive military

alliance with China, and named most of the objectives which were sought

later in the Japanese Demands. It also contained a surprisingly accurate

forecast of Japanese foreign policy as a result of the war.

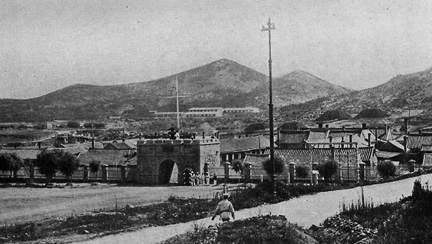

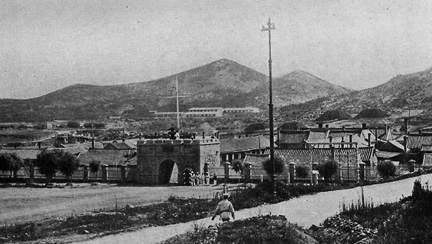

Fig. 2 . An Outpost

of Tsingtao, the German Stronghold in China. The white buildings in the

centre are the German barracks; fortifications and guns are concealed in

the hills in the background. Tsingtao was captrured by Japanese and British

troops on Nov. 16, 1914.

As already indicated in the ultimatum to Germany and in Count Okuma's

message to America, Japan had made statements concerning the return of Kiaochow

and concerning any attempt to secure more territory or privileges from China.

But a change of mind was indicated in December by certain statements made

in the Japanese Parliament by Baron Kato, Minister of Foreign Affairs. Having

been asked if Kiaochow would be returned to China, he stated that the question

regarding its future was at present unanswerable, and further that Japan

had never committed herself to return Kiaochow to China. This changed attitude

was revealed again in the ultimatum which Japan presented to China in May

to force acceptance of the Twenty-one Demands. In this ultimatum Japan used

the non-restoration of Kiaochow as a weapon with which to coerce China into

an acceptance of the Demands. In the ultimatum, she said in part, "From

the commercial and military points of view, Kiaochow is an important place,

in the acquisition of which the Japanese Empire sacrificed much blood and

money, and after its acquisition, the Empire incurs no obligation to restore

it to China." Then, in an accompanying note, she added: "If the

Chinese Government accepts all the articles as demanded in the ultimatum,

the offer of the Japanese Government to restore Kiaochow to China, made

on the twenty-sixth of April, will still hold good." In other words,

Japan was holding Kiaochow as a pawn to bargain with, and would continue

to hold this territory, unless her other demands were satisfied.

The entire group of requests concerning Shantung, as contained in Group

I of the original Twenty-one Demands, was as follows:

GROUP I

"Art. I. The Chinese Government engages to give full assent to

all matters upon which the Japanese Government may hereafter agree with

the rights of the German Government relating to the disposition of all

rights, interests and concessions, which Germany, by virtue of treaties

or otherwise, possesses in relation to the Province of Shantung.

"Art. 2. The Chinese Government engages that within the Province

of Shantung and along its coast no territory or island will be ceded or

leased to a third Power under any pretext.

"Art. 3. The Chinese Government consents to Japan's building a

railway from Chefoo or Lungkow to join the Kiaochow-Tsinanfu railway.

"Art. 4. The Chinese Government engages, in the interest of trade

and for the residence Of foreigners, to open by herself as soon as possible

certain important cities and towns in the Province of Shantung as Commercial

Ports. What places shall be opened are to be jointly decided upon in a

separate agreement."

The second group of demands dealt with the Japanese sphere in Manchuria

and Mongolia. As the result of the war with Russia, Japan had secured a

twenty-five year lease on Port Arthur and control of the neighbouring railways

and Russia's rights in Southern Manchuria. She was looking with longing

eyes towards Eastern Inner Mongolia, but as yet had no rights there. Now,

in a preamble to this second group, Japan stated that the "Chinese

Government has always acknowledged the special position enjoyed by Japan

in South Manchuria and Eastern Inner Mongolia," and demanded a ninety-nine

year lease of Port Arthur and the important railways of that region; and

privileges of trade and mining and residence in both Manchuria and Mongolia

alike. These privileges went far beyond any granted in other provinces of

China. They practically transformed Southern Manchuria and Eastern Inner

Mongolia into Japanese dependencies. The detailed Demands were:

GROUP II

The Japanese Government and the Chinese Government, since the Chinese

Government has always acknowledged the special position enjoyed by Japan

in South Manchuria and Eastern Inner Mongolia, agree to the following articles:

"Art. 1. The two Contracting Parties mutually agree that the term

of lease of Port Arthur and Dalny and the term of lease of the South Manchurian

Railway and the Antung-Mukden Railway shall be extended to the period of

99 years.

"Art. 2. Japanese subjects in South Manchuria and Eastern Inner

Mongolia shall have the right to lease or own land required either for

erecting suitable buildings for trade and manufacture or for farming.

"Art. 3. Japanese subjects shall be free to reside and travel in

South Manchuria and Eastern Inner Mongolia and to engage in business and

in manufacture of any kind whatsoever.

"Art. 4. The Chinese Government agrees to grant to Japanese subjects

the right of opening the mines in South Manchuria and Eastern Inner Mongolia.

As regards what mines are to be opened, they shall be decided upon jointly.

"Art. 5. The Chinese Government agrees that in respect of the (two)

cases mentioned herein below the Japanese Government's consent shall be

first obtained before action is taken:

"(a) Whenever permission is granted to the subject of a third Power

to build a railway or to make a loan with a third Power for the purpose

of building a railway in South Manchuria and Eastern Inner Mongolia.

"(b) Whenever a loan is to be made with a third power pledging

the local taxes of South Manchuria and Eastern Inner Mongolia as security.

"Art. 6. The Chinese Government agrees that if the Chinese Government

employs political, financial or military advisers or instructors in South

Manchuria or Eastern Inner Mongolia, the Japanese Government shall first

be consulted.

"Art. 7. The Chinese Government agrees that the control and management

of the Kirin-Changchun Railway shall be handed over to the Japanese Government

for a term of 99 years dating from the signing of this Agreement."

Japan has not a sufficient supply of iron ore; China is rich in this

mineral; and the solution was obvious. In Group III the largest iron company

in China was to be made a joint concern, and the future mining operations

of the Yangtze Valley were to be placed within Japanese control. The Agreement

read:

GROUP III

"The Japanese Government and the Chinese Government, seeing that

Japanese financiers and the Han-yehping Co. have close relations with each

other at present and desiring that the common interests of the two nations

shall be advanced, agree to the following articles: --

"Art. I. The two Contracting Parties mutually agree that when the

opportune moment arrives the Hanyehping Company shall be made a joint concern

of the two nations and they further agree that without the previous consent

of Japan, China shall not by her own act dispose of the rights and property

of whatsoever nature of the said Company nor cause the said Company to

dispose freely of the same.

"Art. 2. The Chinese Government agrees that all mines in the neighbourhood

of those owned by the Hanyehping Company shall not be permitted, without

the consent of the said Company, to be worked by other persons outside

of the said Company; and further agrees that if it is desired to carry

out any undertaking which, it is apprehended, may directly or indirectly

affect the interests of the said Company, the consent of the said Company

shall first be obtained."

Group IV involved Japanese control over Chinese coasts, which would ward

off any future military measure by another Power. It read:

GROUP IV

"The Japanese Government and the Chinese Government with the object

of effectively preserving the territorial integrity of China agree to the

following special articles: --

"The Chinese Government engages not to cede or lease to a third

Power any harbour or bay or island along the coast of China."

But the real extent of the Japanese ambitions was revealed in Group V.

A new sphere --- Fukien ---was named, and the right to build strategic railways

from the coast up the Yangtse River Valley was requested. In addition, China

was to employ Japanese advisers in political, financial and military affairs;

police-courts in important cities were to be jointly administered; China's

arsenals and war munitions were to be controlled by Japan. These demands,

if granted, would have put China definitely in the position of a vassal

state of Japan. They were practically the same as the terms forced upon

Korea before its annexation. In detail they were:

GROUP V

"Art. I. The Chinese Central Government shall employ influential

Japanese advisers in political, financial and military affairs.

"Art. 2. Japanese hospitals, churches and schools in the interior

of China shall be granted the right of owning land.

"Art, 3. Inasmuch as the Japanese Government and the Chinese Government

have had many cases of dispute between Japanese and Chinese police to settle,

cases which caused no little misunderstanding, it is for this reason necessary

that the police departments of important places (in China) shall be jointly

administered by Japanese and Chinese or that the police departments of

these places shall employ numerous Japanese, so that they may at the same

time help to plan for the improvement of the Chinese Police Service.

"Art. 4. China shall purchase from Japan a fixed amount of munitions

of war (say 50% or more) of what is needed by the Chinese Government; or

that there shall be established in China a Sino-Japanese jointly-worked

arsenal. Japanese technical experts are to be employed and Japanese material

to be purchased.

"Art 5. China agrees to grant to Japan the right of constructing

a railway connecting Wuchang with Kiukiang and Nanchang, another line between

Nanchang and Hangchow, and another between Nanchang and Chaochou.

"Art. 6. If China needs foreign capital to work mines, build railways

and construct harbour-works (including dock-yards) in the Provinces of

Fukien, Japan shall be first consulted.

"Art. 7. China agrees that Japanese subjects shall have the right

of missionary propaganda in China."(4)

These Twenty-one Demands were rather curiously prefaced by the statement:

"The Japanese Government and the Chinese Government, being desirous

of maintaining the general peace in Eastern Asia and further strengthening

the good neighbourhood between the two nations, agree to the following."

They were presented by the Japanese Minister directly to the President,

Yuan Shih-kai. The utmost secrecy was maintained and, when rumours became

current, the Japanese Government officially denied their existence. A month

later, it issued a statement listing only eleven demands, Group V and the

more objectional requests being omitted. On April 26th, in place of the

original Twenty-one Demands, twenty-four were presented with slightly different

wording. On May 7, an ultimatum was sent by Japan, demanding the immediate

acceptance of the first four groups and threatening force if a favourable

answer was not received. The fifth group was to be held over for future

negotiations.

On May 8, China submitted, at the same time affirming in a supplementary

statement that it was forced to take this step and that it would not be

responsible for any consequent infringements upon the treaty rights of other

nations or the principle of the " Open Door."

The conclusion of these negotiations marked the winning by Japan of most

of its original objectives. The hope of making China entirely subservient

had not been realized, but Japan's power over the Republic had been enormously

increased and the acquiring of final control seemed only a matter of time.

The situation was summed up by Dr. Stanley K. Hornbeck, a leading authority

on Far Eastern affairs, as follows:

"Whatever her intentions, Japan has accomplished in regard to China

at least five things: she has consolidated her own position in her northern

sphere of influence, Manchuria; she has driven the Germans out of their

former sphere of influence, Shantung, and has constituted herself successor

to Germany's rights; she has given warning that she considers Fukien Province

an exclusive sphere for Japanese influence; she has undertaken to invade

the British sphere of influence; and she stands in a position to menace

and to dictate to the Peking government. A glance at the map of North China

will show how completely Peking is at Japan's mercy. In control of Port

Arthur and of the Shantung Peninsula, Japan commands the entrance to the

Gulf of Pechili, which is the doorway by sea to Tien-tsin and Newchwang.

In possession of Tsingtao, Dairen, and (virtually) of Antung and Newchwang,

Japan thus commands every important port and harbour of the Yangtse. With

the Manchurian railways penetrating the heart of Manchuria and the Shantung

Railway extending to the heart of Shantung--- and with the right to extend

the latter line to join the Peking-Hankow line --- Japan is in a position,

should she so choose, at any moment to grind Peking between the millstones

of her military machine. So far as strategy is concerned, Japan has North

China commercially, militarily, and politically at her mercy." (5)

The interest aroused among the nations by these negotiations was, of

course, keen, and the matter attracted world-wide publicity. The United

States was the only great power not involved in the war in Europe, and it

was perhaps natural that it should be the one country openly to voice a

protest against the settlement. On May 16 she delivered the following note

to the Chinese Government at Peking and to the Japanese Government at Tokyo:

"In view of the circumstances of the negotiations which have taken

place or which are now pending between the Government of China and the

Government of Japan and the agreements which have been reached and as a

result thereof, the Government of the United States has the honour to notify

the Government of the Chinese Republic that it cannot recognize any agreement

or undertaking which has been entered into, or which may be entered into

between the Governments of China and Japan impairing the treaty rights

of the United States and its citizens in China, the political or territorial

integrity of the Republic of China, or the international policy, commonly

known as the open door policy."

Thus the first year of the Great War brought changes of the most vital

importance to the Orient. Whether or not these changes shall become permanent

can be decided only at the conference which will come at the close of the

world-conflict.

Chapter Two

Chapter Two

Table of Contents

Table of Contents